The Accessibility Scotland 2019 theme was Accessibility and Ethics. Matt May @MattMay travelled from Seattle to encourage us to – Design without empathy. Empathy, we are told, is the key to creating accessible products.

The Accessibility Scotland 2019 theme was Accessibility and Ethics. Matt May @MattMay travelled from Seattle to encourage us to – Design without empathy. Empathy, we are told, is the key to creating accessible products.

Many of us as advocates have relied on appeals to emotion to advance accessible practices. But what happens when it doesn’t work? And what happens when “good people” do the wrong things in the name of empathy?

This is the story of a 20-year veteran in accessibility advocacy, who learns that empathy often does more harm than good, and looks for a better way.

Video

Slides

Download Design without Empathy slides in Powerpoint format.

Transcript

I think a lot of you looked at the agenda before this talk and you saw a lot of great, amazing things like Cat Macaulay, oh, Service Design for Government. Léonie talking about robotics and the robots code. Ashley talking about the autistic and empathy exercises.

Then you stopped and you said…

Design without empathy. You monster, how dare you.

I get it, but I wanted to give you some perspective on why we talk about these things and how people understand it, how people interpret it.

To give you some information that will help you in cases that empathy doesn’t work.

I’m going to tear down some of the concepts of empathy and then hopefully we’ll have time to build it back up at the end.

I saw this blog post by a person named Minter Dial who mentioned that there were eleven sessions at the South by Southwest interactive conference this year that featured the word empathy.

This is one of the common ones.

Designing for the forgotten: Impact behind empathy.

There were apparently 70 sessions, somewhere around that, that had the word empathy in them.

We hear this talk in tech conferences all the time. Oh, you really need to have empathy before you can do this.

This is a data researcher, data philosopher named Phil Harvey who works at Microsoft. You see the slide that’s behind him that says,

“Empathy will make you more successful, achieving intended outcomes, excepted by stakeholders, providing value in a measurable way.”

This is the way that we hear empathy couched these days, in fact Minter Dial himself is very interesting. I listened to this. This was his talk, Heartificial Empathy, which is interesting, and Minter Dial himself has this wizened, silver haired, polymath vibe going on.

That accent that shifts. Is it Belfast? Is it Boston? Is it Brentford? I don’t know. It’s so interesting, but he talks about this specifically. This is funny, because it connects some of the threads that we have here. He talks about empathy as being a good feature in artificial intelligence.

That he talks about not just the kinds of things that Léonie was talking about with the voice inflection and prosody and things, but in terms of not repeating questions, probing, asking more in depth questions. That, that would be a good feature for AI, so that you feel like the computer feels for you.

We’re going to bookmark this for later. There’s some pieces of this that we ultimately find to be fairly problematic, but talks all the time.

Again, another one here. This is a talk featuring a quote by Patti Sanchez.

“The secret to leading organizational change is empathy.”

We keep coming back to this, we keep coming back to this idea that we ultimately can’t really get what we want without feeling empathetic toward other people. In the field of design, the way that we get the word comes from this.

Who’s familiar with this? This is the Nielsen Norman version of the design thinking, who’s actually seen or experienced this particular one?

The design thinking life cycle, and it’s a six step process. It has, as its first step, this idea of empathise.

The language here is, in Nielsen Norman’s terms, is conduct research to develop an understanding of your users. I think understanding is not really a big problem, right? We’re okay wanting to understand who our users are, but there’s so much more loaded into this terminology.

I tease this talk by showing this slide that just says empathy is bad actually.

It’s not all bad, but a lot of it is bad.

The way we talk about it, the way we practice it, the way we covet it, the way we demand it. It changes the way that we think about what this actually means for people.

There’s this book that came out, this is I think from last year called Against Empathy. The author here, Paul Bloom talks through a number of the problems that the idea of empathy, the practice of empathy, the language that we use behind empathy occur.

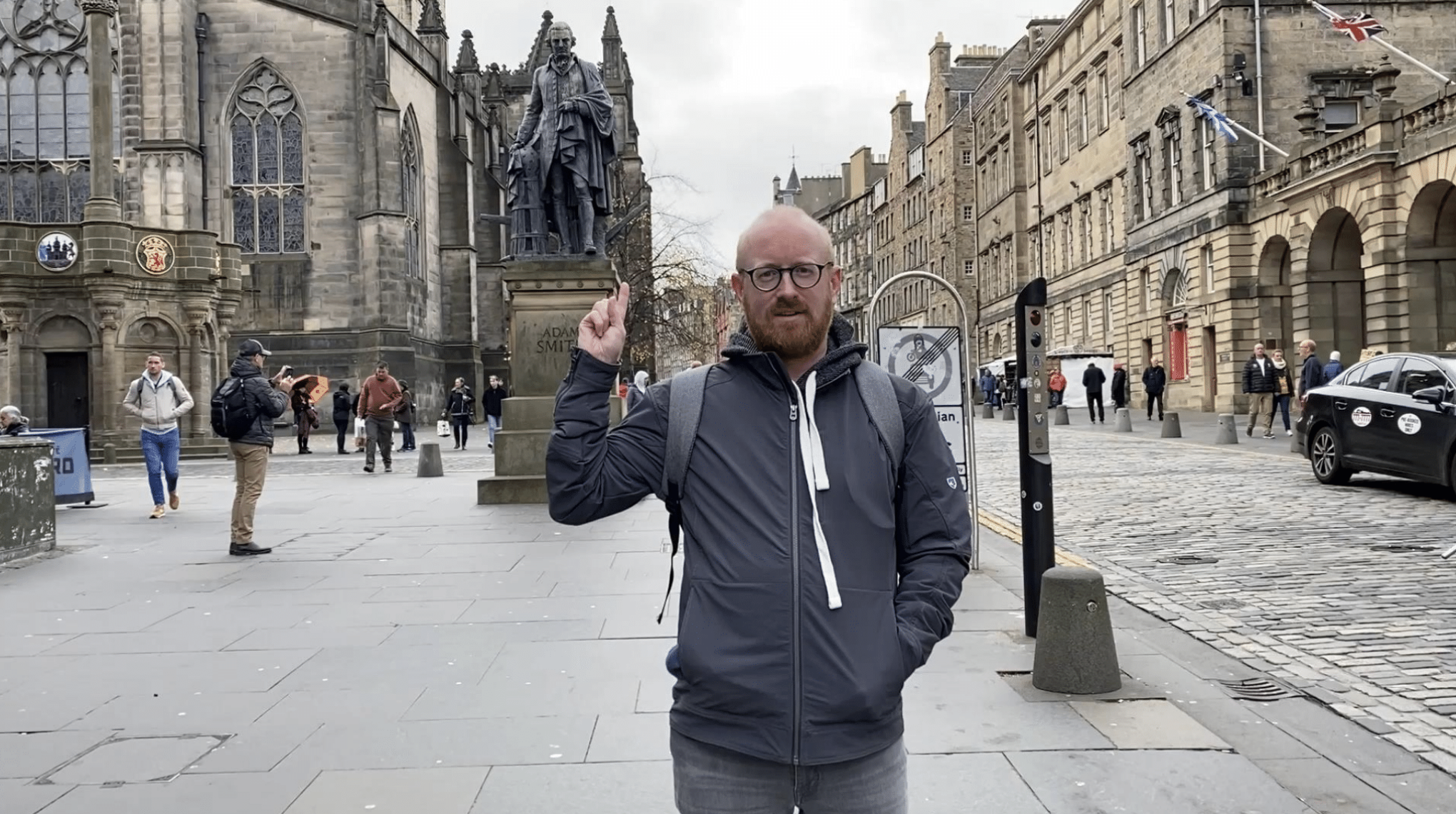

He starts with this gentleman here. This is Adam Smith, or this is a statue of Adam Smith. We don’t know where the real one is right now.

This is the statue that’s on High Street here in Edinburgh. I found a photo of this on Wikipedia, and then I realised – Hey, I happen to be in the city where this statue is.

I decided that I would come and take a photo by myself of this.

Then we took a picture of me here.

And then we made a video.

Yeah, everyone here thinks I’m a libertarian.

The idea of this, of Adam Smith’s concept of what he called sympathy at the time, was this idea of what he called fellow feeling.

Which I’m not sure is really good translation today.

The concept was that you could understand and even feel the emotions, the pain, the frustration that someone might feel as though it were your own. This is from his theory of moral sentiments.

A separate work from all of his libertarian doctrine. This comes from about over 200 years ago and lays the groundwork for what we consider to be empathy today.

The question for me in all of this is, okay, so you have empathy. Okay, so you’ve had this experience with somebody and it is supposed to change you.

That’s not the important part. The question is then what does it make you do? For what reasons? This is really important stuff when you’re starting to think about the meaning of this term. I’ll give you an example of this.

There’s this meme from several years ago.

I wonder if anybody knows what this was referring to, because this is actually a cultural touch point that hit around the world and just blew up and then it disappeared.

This meme is a young woman looking wild-eyed, and at the top it says,

“OMG, soooo inspiring. If you didn’t watch then you’re heartless!!!”

At the bottom it says,

“Doesn’t actually do to help the campaign.”

Does anybody know what campaign this is referring to?

No, Kony 2012, so who remembers Kony 2012? Right? It’s like sheepish, like I got the bumper sticker. This idea of something must be done.

This is something, therefore this must be done, right? This conversation that happens around Kony 2012, so Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda becomes focus of this meme, this campaign that is done by social media experts.

They start selling things willy nilly, bracelets, buttons, posters, all of this stuff about Kony 2012. This thing blows up and it goes away. We’re talking seven years later and the politics of the LRA are out of the picture here. They have a small contingent of soldiers that are there at the end.

What this did was effectively nothing in the grand scheme of things. It caused people, by watching this short video, and then watching the longer video later, to feel this, “I am outraged,” right?

They manipulated people into thinking that they had agency in this process, that they could control what was going on in some other part of the world, because they saw one thing that was tremendously upsetting, right?

They triggered an empathy response, and everybody bit it hook, line and sinker. What ended up happening was that a few people got rich selling doodads, but nothing actually materially happened. Everybody got a chance to feel that outrage and they got to feel like they did something.

That tends to be the pattern when we talk about empathy. I would like to present to you a totally scientific and longitudinal study based on the last couple of weeks of me following the word empathy on Twitter.

I found basically they come down into about five buckets when people use the word empathy in a Tweet.

We use this several thousand times a day on Twitter.

The first category would be in reference to an album by K-pop group NCT that came out in 2018. Any K-pop fans in the crowd? Wrong audience, right?

Second by a brand of wine sold by Gary Vaynerchuk called Empathy Wines.

These are the important three categories here.

One is exhorting other people to feel empathy. This is an absolute good, and it is a quality in people that you should aspire to.

Occasionally we find people who actually cite someone as being empathetic and being happy or grateful for somebody’s empathy.

More commonly is complaining about their group, their in group not being the recipients or beneficiaries of empathy. Now this isn’t a quality, right? This is an accusation. How dare you not have the empathy for these people over here who I just so happen to already identify with, because they’re my friends?

Donald Trump and Brexit, which is the same thing, right? This is the important part about this, the Donald Trump and Brexit empathy things, and I mean do this yourself. Follow the word empathy on Twitter and just watch the thousands and thousands of Tweets go by.

The calls for empathy are coming from both sides of both of these issues. Everybody wants there to be empathy, but they want it to be directed toward themselves and their friends. They don’t want to know every side of a situation, so that they can fully understand where people are coming from.

That is a real problem, because now we’re not thinking about this as being able to truly understand everyone in all situations, but only the ones that we already start to feel something for from the outset.

A Tweet that I thought captured some of the ideas here, is this is actually from Marie van Driessche, who is deaf.

A couple of Tweets of hers that just really resonated with me about this problem.

Ask another Deaf people, people with disabilities to be at your table. Most people are not interested in talking to disabled people, they prefer to empathize. But empathy is not helping us.

— Marie van Driessche (@marievandries) September 4, 2019

Ask another deaf person, people with disabilities to be at your table. Most people are not interested in talking to disabled people. They prefer to empathise, but empathy is not helping us, right?

Now we’re not even talking to the people so that we can empathise, right?

We are just having this good feeling that we’re really good people, because we’re so empathetic. Now we’re allowing that to dictate our next steps.

This is the idea of I feel for you, right? I’ve said that a lot. I have times where I say, “Oh, that’s terrible. I feel for you. This is a bad situation and I want to express that my feelings are with you.”

The modern idea of sympathy, but this is something different. This is I feel for you. My feelings are in place of your feelings in this situation.

That’s a terrible, terrible problem, because now the person that we’re actually ostensibly supposed to be helping is not a part of the equation at all.

I’ll give you an example of a problem here. This is actually a quote from an American politician named Bill Clinton from the 1992 Presidential campaign.

We hear this, I feel your pain, and Americans remember this quote probably above anything else aside from it’s the economy stupid as the catch phrase for the Clinton campaign. We come back to this and we’re like, “Oh, he must’ve been a really empathetic person.”

When he used this, it was to shout down an AIDS protester at one of his rallies. This is the actual quote

“I feel your pain, I feel your pain, but if you want to attack me personally, you’re no better than Jerry Brown,”

more liberal politician that was running for President.

“… And all the rest of these people who say whatever sounds good at the moment. If you want something to be done, you ask me a question and you listen. If you don’t agree with me, go support somebody else for President, but quit talking to me like that.”

That feel like a really empathetic sentence? That idea is critical, the understanding someone’s suffering in the moment and then immediately bringing it back to yourself and how you’re feeling about being attacked in a platform like that.

That is where that disconnect comes from. Let’s go to the other side of this. This is a Tibetan monk named Matthieu Ricard. He is really interesting. He’s been called the happiest person in the world. He’s written multiple books. One of them is called Altruism.

It’s like three inches thick. He is the French interpreter for the Dalai Lama, and he lives in a Hermitage up in the Himalayas. As I was doing the research for this talk, I started to look into this. This is part of the against empathy book.

It talks specifically about Matthieu Ricard. He has this really interesting perspective on this that really resonated with me. It dawned on me that the reason that it resonated with me is that I am also an ordained Buddhist minister, right?

This is empathy at work, right? Somebody that’s like me tells me a story and I start to get it. Before we go any further, well, I do work for Adobe, but when they talk about Adobe Sensei, they’re not talking about me. However, I am an assistant in a Japanese American Buddhist temple in Seattle called Seattle Buddhist Temple.

I’ve studied a lot about Buddhism and I have to practice it particularly with members of my own temple and my own tradition. I want to give a little perspective on the idea of empathy from within that frame and some other ways of thinking about the same idea.

Back to this monk Matthieu Ricard. One of the things that they do with monks, especially people that have a great deal of meditation capabilities, and I’m not one of them, this is actually not part of our tradition to meditate, but they can bring themselves into specific modes, like specific parts of the brain that can be measured.

One of the cases with him was about trying to discern the difference between empathetic action and compassionate action in the brain. They asked him to go into a state of compassionate meditation. Just radiating good feelings at all living things.

He found it pleasant and invigorating to do this for an extended period of time inside an MRI machine. He associated it as a warm positive state associated with a strong, pro-social motivation. They found the part of the brain that was being interacted with.

It was not the part that empathic resonance comes from. Then they asked him to put himself in an empathic state. Now those circuits were being activated, and his brain looked like the people that were asked to think about the pain of other people.

He said –

the empathic sharing very quickly became intolerable to me and I felt emotionally exhausted, very similar to being burned out.

After nearly an hour of empathic resonance, I was given the choice to engage in compassion or to finish the scan.

He switched back to feeling compassionate toward people and immediately his mood was lifted for the rest of the feeling. Empathy itself is exhausting. The idea of taking in everyone else’s suffering, their negative feelings, their pain and making that an inspiration to do good work is going to actually kill you in the process.

We have to think about that …

As opposed to a single experience of empathy, thinking about it as being beneficial.

The longer term idea of this is something that really just is unsustainable in us as a species. This is where I want to talk about the empathy versus compassion.

In Buddhism we have this idea of Karuna, so compassion, and that comes in a couple of different flavours.

What we call empathy colloquially today, in Buddhism we would call emotional compassion. It’s not happening really in our brains, but in our hearts to speak spiritually.

In Buddhism, they talk about this as being a very shallow experience that is something where we are being led by our emotion and that is not a good practice for people to be doing generally in Buddhism. The idea of great compassion or compassionate empathy is more all encompassing.

It is something that not only do you individually feel toward the people that you care about, because that in Buddhism would be attachment, right?

That we have a resonance with the people that are closest to us. Compassion is a much more all encompassing feeling.

We have to understand that we’re all going through some suffering. Suffering in Buddhism is … To talk about this the first noble truth of suffering. You think like all existence is suffering, right? That’s usually what you hear, but the truth is I think the translation that I prefer for that is that suffering is inevitable as a part of life.

We know we’re all going through some suffering right now. It’s a different feeling to know that you are all fellow travelers.

I think if we go back to Adam Smith here and he talked about this idea of fellow feeling. First I want to say like the iPhone camera is spectacular.

I have ADHD by the way. I was going through the slides and I was like, this is really great. The detail up here, this is my dinosaur overlooking Edinburgh. I had to get buddy in the frame, because just every little spot of fuzz is just perfect.

Anyway, back to Adam Smith. Seen here with his pet Dalek apparently.

I don’t know what that is. If somebody can explain to me what it is? Is it a trashcan? Is it a Dalek? Was he really that far ahead of the times? What he said was to contrast compassion and empathy.

His idea of this 225 years ago was that compassion was pity. He said;

“Pity and compassion are words appropriated to signify our fellow feeling with the sorrow of others. Sympathy, now, empathy. Through its meaning was perhaps originally the same, may now, however, without much impropriety made to use to denote our fellow feeling with any passion whatsoever.”

He’s talking about this shallow idea of empathy, of our emotions pulling us in a specific direction.

Then he dismisses compassion completely as being pity.

Now, what we find though in research, and this is actually … Cynthia Bennett and Danielle Rosner from the University of Washington, and they published this paper at Chi, which means that I am at least the second, possibly the third person from Seattle to lecture a bunch of Scots about a leader of the Scottish enlightenment this year.

This talk actually specifically talks about that definition of Adam Smith and David Hume, but points out that there’s a bioethics scholar named Rebecca Garden who says that sympathy and sensibility came naturally to certain bodies, those members of the educated upper classes and not others.

They go on to talk about this idea of empathy being experienced as pity. What Adam Smith is talking about and where we get this Western concept of empathy starts by saying it’s not pity.

Now the research that we talk about in this actually says that it is pity.

We’re following the wrong path here. I mentioned the first noble truth, the idea that we can’t escape the idea of suffering, that all conditioned existence, all of the things that are temporary in this world, they’re temporary, and that we’re interconnected.

The basics of Buddhism, but the important part, and I think the thing that we miss in Western culture when we talk about this is that Buddhism teaches us that this is all an act of treating ourselves like we are a camera seeing the rest of the world.

I saw a great billboard that said,

“You’re not in traffic, you are traffic.”

Yeah, that’s the idea of non-self in Buddhism in a nutshell, right? We’re all in this together. When we start looking at this like we’re just one camera and then everything outside is the world.

Then inside is something different and distinct, that gives us the chance to have this ego moment, which I think it can be tremendously distancing for what we’re actually intending to talk about. I think there’s a video that’s in here.

Let me double check that. No, we’ll keep going on. This concept of empathy, right? We’ve now talked about this is painful to you, right? This is something where you are actually accepting other people’s pain and that it actually causes you stress as a result.

This is before you’re actually doing anything to respond to it, so it’s bad for you. It’s bad for people that it’s supposed to be for, because it allows you to ignore the actual stated intentions and desires of the people that you are feeling empathy for.

Why do we talk about it so much?

I think it’s a little problem called ego. I think it’s a big problem called ego.

I was thinking about this as I was putting this talk together and I’d say – if Adam Smith were here, he would say that empathy is an invisible hand that reaches all the way up over your head and pats you on the back.”

To connect this to the other parts of Buddhism that I wanted to talk about, it’s known as the three poisons in Buddhism, greed, anger and ignorance.

These are the things that will keep you from feeling compassion, from feeling enlightenment.

We can see some of the pieces of this in the way that we talk about empathy.

This is a course that you can fly to Los Angeles and take on December 6th called “How To Influence With Tactical Empathy”. Be heard, overcome objections and close deals with fewer counter offers.

We are literally weaponising empathy.

This is greed, this is greed in a nutshell like this idea that we are going to suddenly by seeming to listen to people.

There’s no listening going on in this conversation, right? This guy looks like what?

Greed is definitely a factor when we start talking about this.

Now, second piece, and this is a Tweet that I posted awhile ago, it said,

Empathetic Person: We added this overlay to our site to read out the content for blind users!

Blind User: um, that’s nice, but I just want it to work with my own screen reader

Empathetic Person: pic.twitter.com/sA6otv7MHi

— Matt May (@mattmay) August 15, 2019

I’ve seen this happen.

Ignorance, this ignorant act, right?

I have decided for the blind user that this is the thing that I’m going to do for you and now I want to be rewarded for it.

The blind user responds, “I don’t care about your damn overlay. I want to use the thing that I want to use.”

What happens? “How dare you? How dare you tell me that this is the wrong thing to do,” right? Obviously this ego is coming into us, right?

I’ve been greedy, I’ve been ignorant and now I’m angry, because the thing that I was told that was going to make me this wonderful enlightened being is now the wrong thing. I have to respond in anger as a part of the process.

I think the problem in a nutshell is the concept of the designer as a center of the universe, right?

They’re in the center of this design thinking thing, right?

What’s the word in the middle? Design, it’s not about people. It’s about being the one that controls the wheel here.

Looking back, going back to this Chi talk. There’s so many quotes from this, I think it’s just really worthwhile finding this talk about the concepts of empathy and the other.

People with disabilities serve as spectacles for designers to look upon for inspiration. They become important for evidencing that empathy was done and that its benefits could be reaped. I want to play this video here from …

This is a good friend of mine named Liz Jackson.

She gave this talk (Empathy Reifies Disability Stigmas) at the Interaction 19 conference in Seattle earlier this year.

1500 designers and you could hear the sound of a pin drop as she was giving this talk, so let me just play this.

I think in all of this we’ve lost the ability to parse out our feelings. I don’t think we know how to separate when we’re feeling pity and when we’re feeling inspiration. For me, I think this disconnect has led to three outcomes. The first is, is it reifies class and power structures, right?

You always have the empathizer and then you always have the empathizee, right? The empathizer is cast as the savior, and the empathizee is always the recipient and those roles never change. Second, it prescribes emotions. I think we’ve caught onto this brand of empathy.

It feels a certain way. I often say that we’ve convinced ourselves that things that feel a certain way do a certain thing, but they don’t. I would even go so far as to say that things that feel a certain way prevent us from doing a certain thing.

The third thing is, is it silences the recipient, right? You are expected to be grateful for that which has been done for you.

Liz Jackson.

That connects to simulation exercises, and I don’t really have anything to counter Ashley’s previous talk. I think that what she did with talking about autism from an autistic perspective is really the only way that simulation can work.

RNIB will sell you a simulation package. You can do that here.

The National Federation of the Blind in the United States is against simulation broadly.

In fact, what they say is that idea of pity, of feeling bad once those goggles were off, the idea that you take the goggles off and you just think, “Thank God that’s not me.”

They said that after the simulations that they had run students reported feeling more vulnerable to disability, less comfortable interacting with disabled people and more pitying toward people with disabilities.

Empathy built through emersion, critics argue, and this is from the Cynthia Bennett, Danielle Rosner paper,

“Empathy built through immersion may steer designers toward narrow and inaccurate conceptions of disability experiences.”

I actually attended this Dialogue in the Dark. This is one in Hamburg, and it was this scattershot, 90 minute just being led around in a completely dark room by someone who is blind.

It gave you this like, I’m confused, I feel a car here. I’m worried about getting hit by a car as I cross the street.

It was confusing enough that it made people feel just generally uncomfortable about the experience.

If you’re going to do simulation, you should be doing it in a very, very narrow band, so that people can understand exactly what is being done. It should be led, it has to be led by somebody that is having that exact experience right now.

This quote probably covers the whole idea.

…Since empathy drives us to seek evidence, it can not be considered evidence itself.

I’ll boil this down a little bit more.

Feeling stuff does not equal knowing stuff, right? Feelings aren’t facts.

They’re facts in a very narrow sense, but they’re not something that you can build upon to arrive at a decision.

It also means it’s not doing stuff.

That feeling that you have, especially if you’re feeling a greater sense of self by being so empathetic, does not make a bit of difference to the people that you are ostensibly supposed to be helping.

Another way of saying this is Elaine Scarry in a paper called The Difficulty of Imagining Other People, that what matters about this is –

“Not in the pleasurable feeling of cosmopolitan largesse, but in the concrete willingness to change constitutions and laws,”

– right?

This is the most critical.

She was talking about cases like slavery in the United States and the occupation of India by the UK.

That it doesn’t matter how you feel about this, if you’re not willing to make some concrete changes to this.

Now that I’m done tearing down all of empathy, I’m going to talk about the ways that we can build this up, so that we can have something that is a better foundation, a better structure for approaching the same problem.

The first we already talked about is compassion.

The idea is to understand and be able to talk to and be willing to talk to everybody that is a part of this system.

I think if anybody’s familiar with systems design, I think that’s just Buddhism for business.

Systems design inside that package has the responsibility to be accountable, to actually understand that you’re doing harm to the system and to be able to call that out, so that you can do better. That is another aspect of professionalism.

Listening to Cat Macaulay talk this this morning, I don’t think she said the word empathy, right?

She’s doing a job. I’m sure that the work that she does resonates with her very strongly as it does with me.

In the end, we don’t need to keep convincing people to be doing this stuff.

We just need to get to the point that this is a part of what we do for a living. This should be our job. This should be the work that we’re doing. By trying to shift back to empathy and just trying to make people feel this stuff over and over again.

When people start to be resistant to it, to the point that they actually feel an aversion, a revulsion to being brought back to it, you need to find other levers to do this.

One of those levers is authority. Once you have codified that this is the thing that you’re going to do, you need to stop fighting the last war, right?

Make it a policy if that’s what needs to be done. If you want to do that, great. If you don’t, then you can find another line of work.

We have to get to the point that this isn’t something that engineers can decide not to do. That designers can decide, I only want to design for the people that I want to design for.

Finally equity.

This cannot be something that is bestowed from on high to on low.

Everybody needs to be at the same level. In order for that to happen, everybody needs to have a place at the table, an equal place at the table. They need to be able to share in the benefits.

They need to be able to share in the struggles that you undergo in order for this to be a truly equitable system.

Going back to Marie van Driessche, this is an example of this.

It struck to me that I’m making things easy for designers without actually talking to me, or another Deaf people/users. I’m often being asked afterwards to check their work but they should ask me during their process. Ask me to think and work *with* them

— Marie van Driessche (@marievandries) September 4, 2019

I call this equity, Liz Jackson calls this – “Mutuality”.

This is a radical act by an individual or group of individuals intended to create space for sustainable participation within a system or institution that benefits from representing or serving them.

Thank you / sorry.